A synopsis of the series’ director

by CapCom

December 2009

Yoshio Sakamoto is the director of the Metroid series and producer of the Wario Ware series. He was the lead designer of Nintendo R&D1, which was reformed in 2005 under Entertainment Analysis and Development; he also served as a development assistant for Nintendo’s Handheld Game Department.

Yoshio Sakamoto is the director of the Metroid series and producer of the Wario Ware series. He was the lead designer of Nintendo R&D1, which was reformed in 2005 under Entertainment Analysis and Development; he also served as a development assistant for Nintendo’s Handheld Game Department.

Yoshio Sakamoto was born in Nara Prefecture, Japan on July 23, 1959. Shortly after graduating from art school, he was hired by Nintendo as a designer. At the time, the company was hiring new talent to expand their videogames division. Sakamoto was recruited by Shigeru Miyamoto and was eventually placed on Miyamoto’s team to help design Donkey Kong Jr (Arcade). He later went on to develop Balloon Fight (NES) after finally finding his way to Nintendo R&D1 under the wing of Gumpei Yokoi, who acted as producer for many of his games.

Sakamoto’s most famous body of work began with his direction of Metroid, which defined an entire genre and the nature of atmospheric level design. Later, he was responsible for the Wario Ware series, which redefined the way we think of games. In these series, we can see the main trademarks of Sakamoto’s work: a desire to produce unique works that challenge his abilities and that help make him stand out from Nintendo’s other designers.

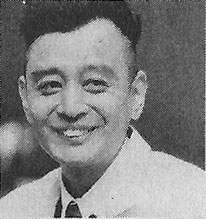

Yoshio Sakamoto, 1994 (Japanese Official Guide)

Sakamoto is also credited with founding Team Shikamaru, a ‘club’ of sorts for scriptwriting at Nintendo. Team Shikamaru has produced several works, most notably the Famicom Tantei Club series. Sakamoto’s skills as a writer can be seen in his writing for Kaeru no tame ni kane wa naru, Metroid Fusion, Metroid Zero Mission, and Super Metroid. You can see a sample of Sakamoto’s design process in his storyboards from the Japanese Super Metroid strategy guide. No doubt this storytelling ability will be taken to new levels with Metroid: Other M.

At the same time, Sakamoto has become a kind of enigmatic director at Nintendo to outsiders, being overshadowed by the work of Miyamoto and Miyamoto’s apprentice, Eiji Aonuma (Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess). In some cases, Sakamoto’s role has been overlooked or underemphasized and credited to Gumpei Yokoi, who served mainly as the producer or supervisor of Sakamoto’s games rather than as a creative director. So Sakamoto is Nintendo’s ‘other’ director, one of the most creative men in the company, yet also one of the least known, considering his body of work. As such, he has not been as widely sought out by the press, but his recent work with Other M is likely to change that, catapulting him into the spotlight.

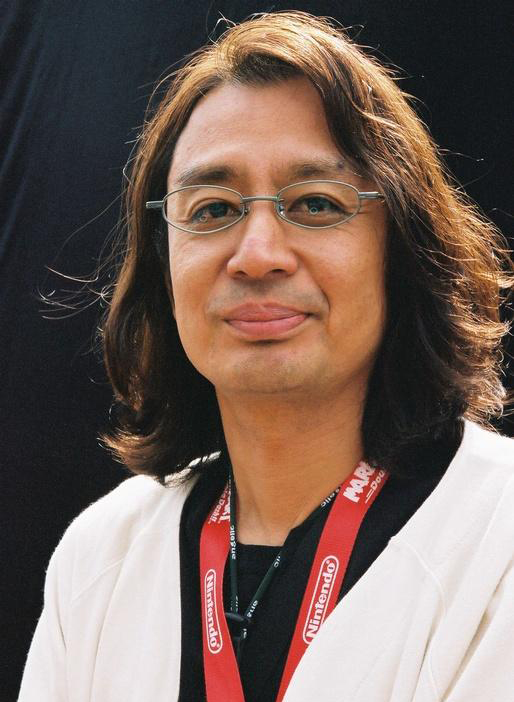

Yoshio Sakamoto, 2006 (Kikizo)

Sakamoto’s main drives in design are to continually produce something new that challenges both what his team and he himself are capable of doing as well as expanding the styles of gameplay that are possible within the medium. This comes from his primary goal of differentiating his work as much as possible from that of his colleague and former mentor, Shigeru Miyamoto. While he looks up to Miyamoto’s work and the two are close friends, he recognizes that it is impossible to compete with Miyamoto on the same field and would rather not be compared with Nintendo’s most famous designer. Aside from leading to the production of games that are unique even within Nintendo, this seems to be one of the main drives behind Sakamoto’s desire to create something new and challenging, though it also seems characteristic of him as an individual. Note that Team Ninja also has these philosophies, making the two teams well-attuned for Project M. This desire for challenge and uniqueness has also lead to the reasons for why Sakamoto has not produced sequels for the sake of making sequels (as might be said of the Castlevania series) or ported older versions of games to the Game Boy Advance (as was done with Nintendo R&D2’s ports of old Super Mario Bros. games to the Game Boy Color and Game Boy Advance) and is the reason why Metroid II and Super Metroid have not been remade.

Yoshio Sakamoto and Miyuki Miyabe, 2003 (Hobonichi)

This drive has also allowed Sakamoto to collaborate with other team members within Nintendo as well as with teams outside the company. These achievements include the formation of Team Shikamaru, a group, or perhaps ‘club’, dedicated to scriptwriting, and also included his collaboration with Intelligent Systems in the design of Super Metroid. In the latter case, artists and designers at Nintendo R&D1 collaborated with Intelligent Systems programmers to produce one of the greatest games of all time, allowing the programmers to push the limits of what the Super Nintendo hardware was capable of doing so that the artists could in turn express themselves to the fullest within those boundaries. This has finally culminated with the interstudio collaboration with Tecmo’s Team Ninja and D-Rockets to create Project M, something that has never been done at Nintendo before, but which we may be seeing more of in the future.

Finally, Sakamoto adopts unique design techniques for the creation of his games. First, his design philosophy has shifted from a top-down system where Sakamoto dictates everything that will go into the game (which was used in Metroid Fusion) to a collaborative brainstorming effort where each team member is encouraged to present ideas early on in the design process, which are later whittled down to the game’s core (note that something similar seems to have been used as far back as the original Metroid when Hirokazu Tanaka contributed to the names of many of the characters). This technique was formalized from the production of the minigames in WarioWare, Inc. where each team member designed their own minigames on Post-It Notes and left them on Sakamoto’s desk; it was later applied to Metroid Zero Mission’s design where each team member indicated what they would like to see in the game.

Yoshio Sakamoto, 2003 (Official Nintendo Magazine)

Yoshio Sakamoto, 2001

Second, Sakamoto follows in the footstep’s of Shigeru Miyamoto’s ‘over-the-shoulder’ gameplay. As early as Super Metroid (1994), and likely before, Sakamoto had been holding ‘run-through meetings’ where his team would bring in players from both inside and outside the department who had never seen the game before and observe them playing the game the whole way through. This over-the-shoulder feedback may have been gained from working with Miyamoto, as it is a central point of the master’s iterative design style. In addition, Sakamoto is not afraid to take his games home to have his wife and kids play them for a completely unique perspective (though perhaps this is not done as commonly as he was able to back in 1994 due to increased security; note that Miyamoto also judges his games’ successes by how much his wife likes them).

Yoshio Sakamoto and Yosuke Hayashi, 2009 (Wired)

One of Sakamoto’s unknowns seems to be working with modern home console technology. While he is very skilled at high-level design, Sakamoto has not worked directly as a designer or director on a 3D adventure game. As a result, his design skills of 3D action games have yet to be expressed, which could add to the uniqueness of Other M or perhaps leave it slightly off the mark. However, the strong designers at Team Ninja should be more than enough to make up for this, and so we have high hopes that Project M will deliver and be a truly unique expression of the 3D action/adventure game.

Masterpiece: Super Metroid

Super Metroid has so far been Sakamoto’s masterpiece (we’re still waiting to see if Other M will surpass it). While Sakamoto has produced many fantastic games from this point, there is no doubt that Super Metroid still stands as the greatest game he has created so far, and there seems to be a formula that lead to its success: a small, cohesive and collaborative team; young, eager talent with some experience directed and apprenticed by senior veterans; and a generous but directed development schedule.

Super Metroid had an average-sized development team for the time at 17 people, including five artists and two composers from Nintendo along with eight programmers from Intelligent Systems (IntSys). The game thus had a strong collaborative element where the artists, particularly art director Tomomi Yamane, would talk with the programmers to find out what the Super Famicom hardware was capable of producing and then direct to his artists the kind of graphics and designs that could be implemented within those limitations. Yamane was also able to formalize the design of all the characters and areas, ensuring a consistent style throughout the game; Super Metroid’s strong art design might not have been possible without his hard work.

In addition, most of the IntSys staff was very young, between the ages of 20 and 25, while one programmer, Motomu Chikaraishi, was only 17 when the game was completed. However, many of them had worked on at least one game prior to Super Metroid, and so this was not their first title. These younger programmers were directed by senior Kenji Imai. Most of the art direction staff was in the late 20s or mid-30s, having cut their teeth on Famicom classics such as Kid Icarus and the original Metroid, when they themselves were in their late teens or early 20s. This combination of experience with young talent was something that must have given the team great energy as well as the wisdom of experience and direction to keep the project focused.

Super Metroid was also granted a relatively long development cycle of two and a half years from pre-production to final build, even while most other Nintendo development teams were producing games in much less that time. The longer cycle, together with the team’s strong direction, resulted in a game that was thoroughly polished and wonderfully delivered. Note, however, that there is a difference between having all the time in the world and being given only enough time to finish the project: a game must have strong goals and deadlines (which seem to have been strictly enforced upon producer Makoto Kanoh by Gumpei Yokoi) or it will remain forever in development, as was the case with Duke Nukem Forever. With Super Metroid, all of these steps came into place to produce one of the best games of all time.

Super Metroid introduced many unique elements to gameplay, such as the Grapple Beam (which has forerunners in Bionic Commando), the Wall Jump (which has been used in many videogames since), and the Speed Booster. Additionally, Super Metroid is famous for introducing a level of environmental storytelling that has not quite been seen since where story is told through gameplay and the actions of characters rather than through text or cutscenes, a technique that culminated in the epic battle between Samus and the Mother Brain and the sacrifice of the Baby Metroid. It truly demonstrates some of the storytelling potentials of the medium.

Yoshio Sakamoto, 2009 (Kotaku)

At the same time, Super Metroid was not bulletproof: new abilities such as Wall Jump and Shinespark had not been thoroughly tested by the development team, and as a result, these allowed for the discovery of sequence breaking by many intrepid Zebesian explorers. While these might be seen from one perspective as flaws in the intended design, they provided a positive benefit: sequence breaking allowed players to challenge the system to beat their best times, and allowed for a type of player expression and virtuosity that has helped make Super Metroid even more of a classic than it already was. Many developers have learned from this and have purposefully built sequence breaking into their games (Shadow Complex) while Yoshio Sakamoto has applied the nonlinear sequence breaking gameplay and player virtuosity into the puzzles and level design of Metroid Fusion and Metroid Zero Mission.

A sequel to Super Metroid was not produced for nine years. Sakamoto had initially intended the Metroid series to end with Super Metroid, a bold move for a videogame, but in addition, he was also busy working in Nintendo’s handheld game department on the Virtual Boy, Game Boy Color, and Game Boy Advance, and so did not have the resources to work with Nintendo 64 technology, which he viewed as incapable of producing the visual assets required for a realistic action game. (The Game Boy Color was also viewed as too limited because he felt games made on the console would be unfavorably compared with Super Metroid). While it seems there had been ideas at the time for a new Metroid, Sakamoto simply did not have the resources or technology to make the game he wanted, and so it was not until the Game Boy Advance that he had the technology and the skills to produce what he wanted.

Yoshio Sakamoto, 2009 (Retro Gamer Magazine)

Bibliography: List of Yoshio Sakamoto Interviews and Related Information

[3] N-Sider N-Sider Overview (with pictures)

[4] Metroid designer Yoshio Sakamoto speaks! – Interview (Computer and Videogames, Sept 1, 2003)

[5] Metroid: Zero Mission Director Roundtable – Interview (IGN, January 30, 2004)

[6] When Samus Was Naked – Interview (Japanese Official Super Metroid Strategy Guide, translated by Devin Monnens, aka CapCom)

[7] Q&A: Yoshio Sakamoto, Yousuke Hayashi on Metroid: Other M – Interview (Wired, June 16, 2009)

[8] Miyamoto Questions Metroid Director, Metroid Guy to Xbox Guy to PS3 Guy – Chain Interview (Kotaku, June 15, 2009)

[9] Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Samus But Were Afraid to Ask – Interview (Game Players, Vol. 7, No. 5, May 1994)

[10] Nintendo R&D1 Interview with Wario Ware Team – Interview (Video Games Daily, April 7, 2006; on Wario Ware)

[11] Metroid Other M Preview Interview – 1Up (June 3, 2009)

[12] Ask Dan Interview with Dan Owsen – Metroid Database

[13] The Making of Super Metroid Interview (Retro Gamer Magazine, Issue 65. July 2009)

[14] Making Shadow Complex Interview with Donald Mustard (Gamasutra, August 28, 2009; Shadow Complex)

[15] Interview with Donald Mustard (Play Magazine, July 2009; Shadow Complex)

[16] Nintendo Online Magazine Interview (Japanese, Nintendo Online Magazine; this has been partially translated).

[17] Nintendo Interview (Japanese, Official Prime and Fusion page; not translated yet)

[18] Miyki Miyabe Interviews Yoshio Sakamoto (Japanese, Hobonichi; not translated yet)

Yoshio Sakamoto, 2003 (Hobonichi)

Known Credits

Donkey Kong Jr. (1982) – Designer

Balloon Fight (1985) – Director

Metroid (1986) – Director

Kid Icarus (1986) – Game Design

Ginga no Sannin (1986) – Director?; port of The Earth Fighter Rayieza (Enix, MSX)

Famicom Detective Club (1988) – Director, Writer

Balloon Kid (1990) – Director

X (1992) – Director

Kaeru no tame ni Kane wa Naru (For the Frog the Bell Tolls) (1992) – Scenario

Hello Kitty World (1992) – Special Thanks

Super Metroid (1994) – Director

Teleroboxer (1995) – Director

Galactic Pinball (1995) – Special Thanks

Game & Watch Gallery (1997) – Adviser

Famicom Detective Club Part II: Ushiro ni Tatsu Shoujo (1998) – Director, Writer

Trade & Battle: Card Hero (2000) – Director

Wario Land 4 (2001) – Supervisor

Metroid Prime (2002)- Special Thanks (Content Advisor)

Metroid Fusion (2002) – Chief Director

Wario World (2003) – Advisor

WarioWare, Inc.: Mega Party Game$ (2003) – Supervisor

WarioWare Touched! (2004) – Producer

Metroid: Zero Mission (2004) – Chief Director

Metroid Prime 2: Echoes (2004)- Special Thanks (Content Advisor)

Metroid Prime Pinball (2005) – Special Thanks

WarioWare: Smooth Moves (2006) – Producer

Rhythm Tengoku (2006) – Producer

Picross DS (2007) – Localization and Testing Supervisor

Metroid Prime 3: Corruption (2007) – Special Thanks (Content Advisor)

Metroid: Other M (2010) – Director

Rhythm Heaven Fever (2011) – General Producer

Kiki Trick (2012) – Supervisor

Game & Wario (2013) – Producer

Tomodachi Life (2014 – Producer

Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS (2014) – Original Game Supervisor

Rhythm Heaven Megamix (2015) – General Producer

Metroid: Samus Returns (2017) – Producer

Super Smash Bros. Ultimate (2018) – Original Game Supervisor

Famicom Detective Club: The Girl Who Stands Behind (2021) – Producer, Original Game Design / Scenario

Famicom Detective Club: The Missing Heir (2021) – Producer, Original Game Design / Scenario

Wario Ware Get it Together! (2021) – ? (Producer likely)

Metroid Dread (2021) – Producer

Collaborative Projects

Team Shikamaru

Project M